Designing a narrative game for learning has not been without its roadblocks, though a majority of them have been entirely unrelated to design or development. If I were to change these things, I would naturally remove the tragedy and illness which struck in force around this time, as well as the late night, caffeine-fueled haze in which my final concept emerged. Imperfect circumstances being what they are, it would have served the design process well if I had worked through it gradually, allowing ideas to steep before committing them to the page. Creative work under constraints is valuable and has potential to bring forth meaningfully distinct results compared to a drawn out process. Given the choice, however, I would always pick a slower burn.

An additional consequence of the sprint approach is a lack of feedback. I spun up a concept for an ecology-based game early in the process, which I presented to my classmates as the project I would work on. Unfortunately, I was truly unsatisfied with the idea and quickly shifted focus to something else entirely, which negated many of the clarifying questions and critiques I received. I have always worked best in solitude, and I am comfortable with my ability to draft concepts without external feedback. At a certain point, however, feedback becomes a necessary component to creative works. Without that, I have little knowledge of how closely the pieces match my vision when viewed from the side of the user.

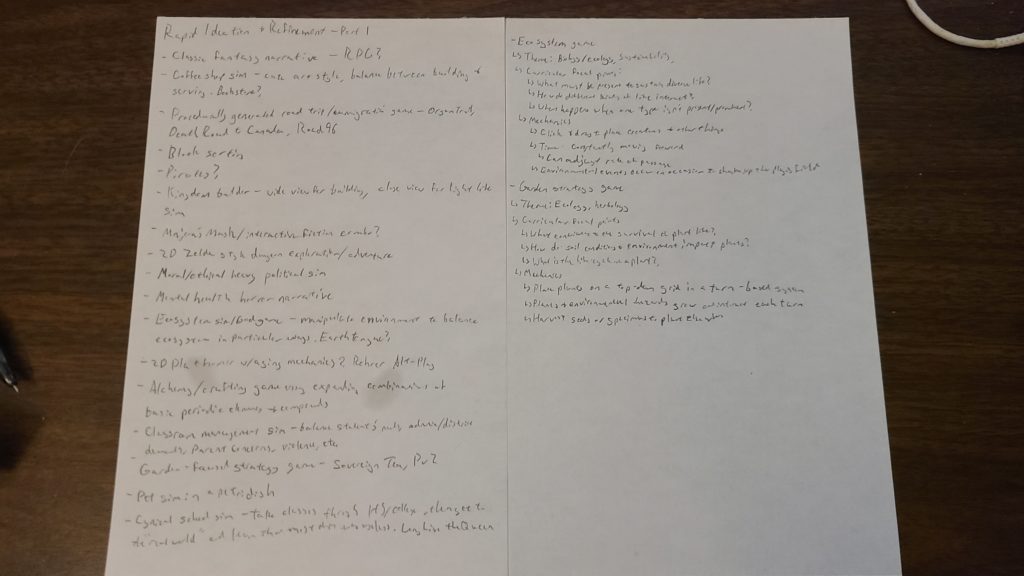

As for the process itself, the most meaningful changes and realizations came from the earlier portion. The ideation process provided numerous ideas, particularly from simply writing down whatever concepts came to mind. When mulling over assignments or other projects under specific constraints, I have a tendency to pre-screen every idea; stopping this instinct allowed interesting concepts to develop more over time. The story building steps, meanwhile, forced me to recognize that the idea I had been tossing around was ill suited for this project. I took a different approach to rethink my core concept, starting from topics I was comfortable with teaching before weaving them into a narrative I liked.

Admittedly, I took less away from the later steps in the design process. I’m willing to mostly attribute the issue to exhaustion setting in by the time I worked on them, but the later steps ended up bringing more elaboration than refinement. Learning objectives in particular are a weak point; I may revisit them with other concepts when I have time, to ensure that I have proper practice.

The working title for the game is Don’t Let Your Dreams Be Beans, which was goofy enough to make me chuckle when I settled on the idea at about 3AM. I am of a mind that even a game with serious intentions should not be afraid of having a bit of fun, so the name has stuck—though the coffee-related leanings certainly help. Broadly, the learning concept is personal development, and the most specific learning objective is that, after playing, users will be able to create clear, actionable goals using the SMART framework. Quite simply, the SMART framework provides structure for five key attributes of an effective goal: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely. This framework is best suited for short-term goals, which complements the secondary focus on breaking down large tasks.

In Don’t Let Your Dreams Be Beans, the player takes the role of a modern-day career counselor meeting a new client over coffee. Over the course of three biweekly sessions, the player helps their client find a field to explore, break down that exploration into steps, and set an actionable goal to pursue next. The primary conflict, as such, is person versus society; the client’s battle against the job market drives them to the player, who helps them overcome it. In the end, the player receives an update on the client’s status six months after their meetings, which sheds light on the impact of their guidance.

Major choices, as represented by unrounded rectangles in the chart at the end of this post, impact where the client goes in response to the player’s guidance. However, as the story focuses on their meetings, the minor choices which reinforce or undermine this guidance determine the branches the player experiences. In the current plan, the branches generally impact where the client starts in subsequent sessions and how effectively the plans they make come to fruition. This is subject to change; I do not have any early endings in mind, which would both trim down the number of endings at the maximum depth and simplify later sessions.